Washington’s kelp forests rely on cool weather and cold water to grow, and are sensitive to changes in climate processes, according to a recent study of the iconic seaweed that grows along the saltwater shorelines of Puget Sound and the outer Pacific coast.

Like coral reefs and rain forests, kelp is a foundation species that supports a unique and diverse community of animals.

That’s why Helen Berry, a scientist with the Washington Department of Natural Resources, teamed up with Dr. Cathy Pfister of the University of Chicago and Dr. Tom Mumford, Marine Agronomics (retired WDNR) to look at the health of kelp forests along Washington’s shores and study the factors that influence their growth or decline.

Using climate data, historical kelp surveys and DNR’s unique 26 year monitoring data set, the research team explored the dynamics of kelp forests along the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Pacific coast.

The research has just been published in the Journal of Ecology.

Looking through the historic lens

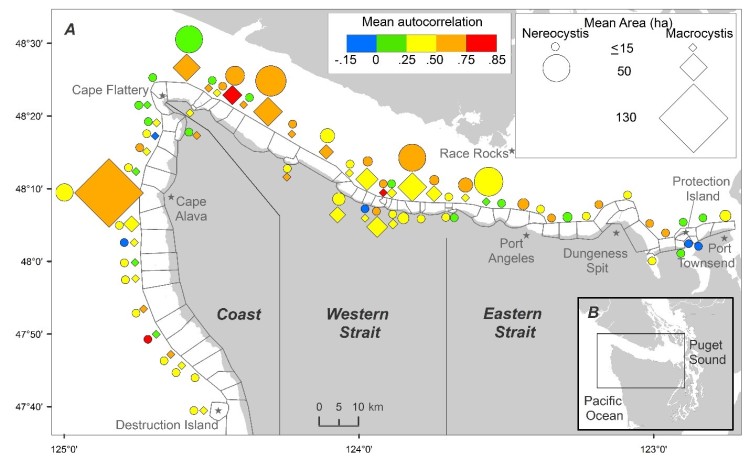

The team’s study found kelp forests were most abundant and persistent along the western Strait of Juan de Fuca and the outer coast, remaining stable when compared to historical kelp surveys done in 1911- 1912. Meanwhile, kelp forests declined in the eastern Strait over that same time. The proximity of kelp forests to human population centers and their distance from the influence of cooler oceanic waters may explain this century-scale decline. Worldwide, kelp dynamics vary greatly – extreme losses were recorded recently in Tasmania and northern California, while other areas show stability or gains.

In contrast to the outer coast and western strait, scientists are concerned about declines in kelp forests within Puget Sound. DNR scientists are currently completing a study that examines changes in South Sound over the last century.

- Abundance and persistence of giant kelp (Macrocystis) and bull kelp (Nereocystis) canopies between 1989 and 2015. The symbol shape depicts species. The size depicts abundance. The color indicates how consistent in abundance each population has been over the last 26 year – more red colors are more consistent through time. (Figure 1 in Journal of Ecology publication.)

Conditions more important than competition

Along Washington’s shoreline, some kelp beds persist over decades, others fluctuate greatly year-to-year. The long-term data set allowed the researchers to detect climate signals in the dynamics of kelp forests. Throughout state waters, kelp cover was strongly related to large scale climate indices. Increased kelp cover occurred when the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the Oceanic Niño Index were negative and the North Pacific Gyre Oscillation was positive, conditions where seawater is colder and more nitrogen rich.

The 2 species that compose kelp beds, the annual bull kelp Nereocystis luetkeana and the perennial giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera have positively correlated dynamics: a good year for one species is also good for the other. This suggests that environmental conditions are more important than competition between species.

How will kelp forests will be affected as our oceans change?

The climate index correlations showed lower kelp forest abundance during warmer water phases. Additionally, a 93-year temperature record in the region revealed a 0.72-degree Celsius increase over this period. The responsiveness of kelp to climate indices, coupled with increasing temperature and increasing human population, suggests a need for wise management to protect this iconic resource.

More information

Read the complete scientific publication at the Journal of Ecology.

Explore the historical and modern surveys in a storymap.

Find out how DNR is working to study Washington’s nearshore environments to strengthen its management of 2.6 million acres of state-owned aquatic lands at www.dnr.wa.gov/programs-and-services/aquatics/aquatic-science.